Workers Battle Drought, Starvation and Superstition

June 22, 2017

The weary young mother in the drought-stricken, West African country of Niger had already seen two of her children die from starvation. Now her son Adamou*, born in her mud hut in Tsaboudey village in Niger's Sahelian southwest, was acutely malnourished, his skin clinging to his bones.

Adamou had never received any medical treatment. In her native Kollo District, Samira had taken him to traditional healers, whose ritual incantations, koranic verse recitations and attempts to make contact with spirits via plants and perfumes had not protected Adamou from the ravages of Niger's drought.

More than 80 percent of Niger's people are Muslim, though many practice their religion alongside the animistic rituals of their ancestors. In Samira's area, traditional healers and marabouts (Muslim holy men) discourage people from seeking treatment from medical clinics. They gave her little hope of recovery for Adamou.

"The child is severely malnourished," the ministry

director said, "and as usual the parents came very late to the health

center after visiting several marabouts."

"The native healer told me that the spirits are not happy about me, and that I have to pay with my children," she said.Many rural people in Niger are deeply suspicious of modern medical practices, and Samira's neighbors were continually frustrated when they urged her to take her children 22 miles away to an indigenous ministry's medical clinic in Dantchandou. At the clinic another toddler, 19 months old, was suffering from Kwashiorkor – the protein deficiency that leads to a swollen belly – along with anemia and diarrhea.

"One week after the admission, the mother ran away with the child to a marabout," said an indigenous medical missionary at the clinic. "She came back two weeks later, when the child was in bad condition." He offered himself consolation with a final thought: "Only God is in control."

Another mother at the clinic was suffering from mastitis, an infection not from drought or malnutrition but a common breast inflammation during breastfeeding. The precarious condition of her baby went from bad to worse.

"The child cannot continue the breastfeeding because of the condition of the mother," the doctor said. "Therefore, the child is severely malnourished, and as usual the parents came very late to the health center after visiting several marabouts."

Some people avoid the clinic because of its Christian leadership. Enough Muslim animists seeking treatment eventually have put their faith in Christ that area religious leaders advise against it. The grandmother of a baby who refused to nurse his first three weeks of life said the family initially declined to bring him to the clinic.

"We were advised to come here with the child, but at first we refused, because we were told that once you come here, you will be Christian," she said.

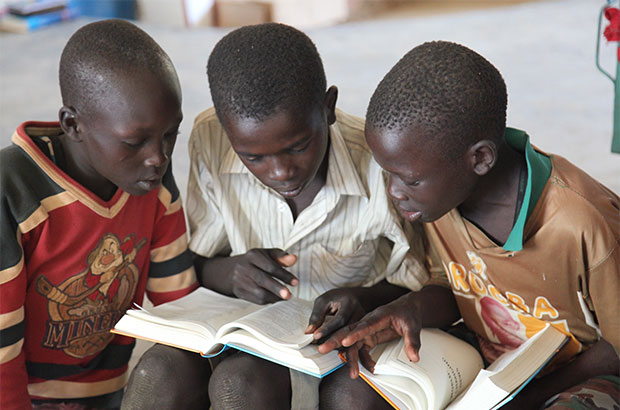

The indigenous ministry director that oversees the clinic said personnel are gentle, tactful and wise in sharing the reason for their hope within.

"In our experience, most people are open to listening [to the gospel]," he said. "The decision to follow Christ may not come immediately, as some plant, and others water, and others harvest. Over here, it's basically a one-on-one thing with lot of patience, as God does His work through their hearts."

The impoverished country of mostly Saharan Desert and some semi-arid Sahel is home to several tribes, including Hausa (slightly more than half the population) Zarma-Sonrai, Tuareg and Fula, and nine official languages besides French – Arabic, Buduma, Fulfulde, Hausa and Tamasheq, among others. Amid this complexity, indigenous missionaries are in prime position to understand and minister to the unique, multilayered characteristics of the various micro-cultures.

Suffering alongside those they're serving, the indigenous teams are enduring the drought in the Sahel region of West Africa that is threatening 1 million children with severe malnutrition. As malnutrition rates are reaching 15 percent in Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali and northern Senegal, food prices in the region have risen 20 to 25 percent over the past five years and could reach 30 percent by August.

As many as 13 million people are expected to suffer the effects of drought this year, such as Samira and the young son becoming weightless in her arms. Recently her neighbors finally persuaded her to take Adamou to the clinic in Dantchandou.

"At the clinic, she had it explained to her that it's just a problem of food," said the director of the ministry, which is assisted by Christian Aid Mission. "The child is malnourished. By the grace of God, he will be fine again. We referred him to a hospital for further management. We are following up on the case, and the mother says, 'I'm very happy.'"

Most of the parents who arrive at the clinic return, he said.

"The mothers are always happy and appreciate a lot what they are receiving all the time from us," he said. "Most of them are thankful now and smiling when they come to the center. A lot of lives are changing. Thanks a lot for all your support, especially your prayers toward us."

To help indigenous missionaries to meet needs, you may contribute online using the form below, or call (434) 977-5650. If you prefer to mail your gift, please mail to Christian Aid Mission, P.O. Box 9037, Charlottesville, VA 22906. Please use Gift Code: 511HIS. Thank you!

CINCINNATI, OHIO (ANS – June 19, 2017)

-- The American student who was released last week after being held in

captivity for more than 15 months in North Korea has died, his family

says.

CINCINNATI, OHIO (ANS – June 19, 2017)

-- The American student who was released last week after being held in

captivity for more than 15 months in North Korea has died, his family

says. “It

is our sad duty to report that our son, Otto Warmbier, has completed

his journey home. Surrounded by his loving family, Otto died today at

2:20pm,” a statement from his parents, Fred and Cindy Warmbier, said.

“It

is our sad duty to report that our son, Otto Warmbier, has completed

his journey home. Surrounded by his loving family, Otto died today at

2:20pm,” a statement from his parents, Fred and Cindy Warmbier, said. He

appeared emotional at a news conference a month later, in which he

tearfully confessed to trying to take the sign as a “trophy” for a US

church, adding: “The aim of my task was to harm the motivation and work

ethic of the Korean people.”

He

appeared emotional at a news conference a month later, in which he

tearfully confessed to trying to take the sign as a “trophy” for a US

church, adding: “The aim of my task was to harm the motivation and work

ethic of the Korean people.” I

had not expected to be staying in such a huge hotel when I arrived in

Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital city, on the first day of my trip. It

was the twin-towered Koryo Hotel, which at 469 feet, is one of the

tallest buildings in Pyongyang. In fact, it is a major landmark there.

I

had not expected to be staying in such a huge hotel when I arrived in

Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital city, on the first day of my trip. It

was the twin-towered Koryo Hotel, which at 469 feet, is one of the

tallest buildings in Pyongyang. In fact, it is a major landmark there. During

meal-times, even though there were only about 10 guests in the entire

hotel, we were ushered each time to the same table in the massive

restaurant. We all noticed that there was a flower pot on it, in which,

we assumed, was hidden a microphone. So, we kept our mealtime

discussions down to a minimum.

During

meal-times, even though there were only about 10 guests in the entire

hotel, we were ushered each time to the same table in the massive

restaurant. We all noticed that there was a flower pot on it, in which,

we assumed, was hidden a microphone. So, we kept our mealtime

discussions down to a minimum. After

a week of wondering if I would get a tap on my shoulder in the very

hotel where Otto Warmbier was later arrested, and I would be

incarcerated and put on trial for my critical broadcasts, we packed our

bags and were ferried back to Pyongyang Airport, and soon we were

winging our way back to Beijing -- and relative safety.

After

a week of wondering if I would get a tap on my shoulder in the very

hotel where Otto Warmbier was later arrested, and I would be

incarcerated and put on trial for my critical broadcasts, we packed our

bags and were ferried back to Pyongyang Airport, and soon we were

winging our way back to Beijing -- and relative safety. About

the writer: Dan Wooding, 76, is an award-winning journalist who was

born in Nigeria of British missionary parents, Alfred and Anne Wooding

from Liverpool, now living in Southern California with his wife Norma,

to whom he has been married for 54 years. They have two sons, Andrew and

Peter, and six grandchildren who all live in the UK. He has a radio

show and TV shows all based in Southern California, and has also

authored some 45 books, and is one of the few Christian journalists to

ever be allowed to report from inside of North Korea.

About

the writer: Dan Wooding, 76, is an award-winning journalist who was

born in Nigeria of British missionary parents, Alfred and Anne Wooding

from Liverpool, now living in Southern California with his wife Norma,

to whom he has been married for 54 years. They have two sons, Andrew and

Peter, and six grandchildren who all live in the UK. He has a radio

show and TV shows all based in Southern California, and has also

authored some 45 books, and is one of the few Christian journalists to

ever be allowed to report from inside of North Korea.